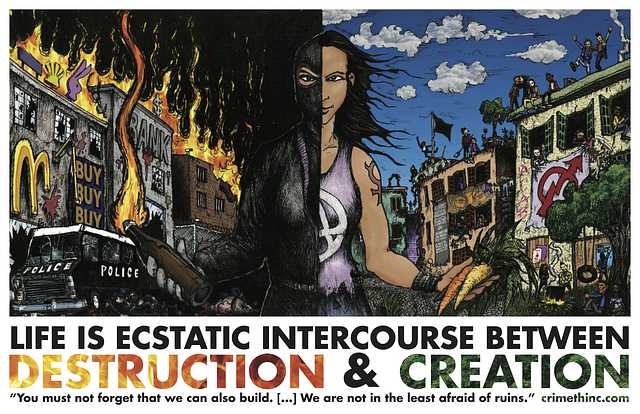

This poster combines imagery and text from our forebears, crystalizing how earlier generations of anarchists saw the relationship between resisting the existing order and building alternatives to it—between destruction and creation. Below, we trace the history of each element of the poster.

The Illustration

This illustration originally appeared in 2001, at the high point of a wave of anti-capitalist activity sometimes referred to as the “anti-globalization movement,” in a 7” record by the Danish anarchist punk band Paragraf 119. Named for the article of Danish law that prohibits the injuring of government officials (“And if a cop wants to pay with his life—it’s OK with us”), Paragraf 119 emerged from the punk, squatting, and anarchist movements in Copenhagen in the 1990s, concentrated around the historic squatted social center Ungdomshuset. In another album by Paragraf 119, the photos of the various band members show each of them getting arrested in some breach of “public order.” This is punk at its best—not as a style of music, but as a culture of resistance in which the songs derives their power from the shared activities of the performers and listeners, whose collective efforts created a space in which these anthems had real meaning.

The cover of the 7” record by Paragraf 119 in which this poster art originally appeared.

Remember them, each and every one, until the day we strike back

Remember every beating, remember every imprisoned activist

Remember the broken comrades, every murdered anarchist

Remember the trumped up charges, remember every injury

Remember all the unjust acts committed by those in power

Nothing forgotten, nothing forgiven-Paragraf 119, “Intet Glemt, Intet Tilgivet” (“Nothing forgotten, nothing forgiven”) on the “Musik til Ulempe” 7”

The Text

As far as we can tell, the slogan “life is ecstatic intercourse between destruction and creation” first appeared on the cover of the fifth issue of the eco-anarchist periodical Live Wild or Die! Issues of Live Wild or Die! don’t include dates, but it appears to have been produced in newsprint around 1994 in Berkeley, California.

Along with Do or Die (and later, Disorderly Conduct), Live Wild or Die! served the most radical and uncompromising elements of the ecological movement in an era before most participants had consistent internet access. You can find the first three issues here.

From the cover of Live Wild or Die! #5.

Finally, the smaller text on the poster is excerpted from a well-known interview with the Spanish anarchist Buenaventura Durruti that appeared in the Toronto Daily Star on August 5, 1936. This interview remains relevant today, when the latest administration to come to power in the United States purports to oppose fascism, yet continues to prioritize repressing anarchists and other anti-fascists:

“The masses are in arms. The army does not count any longer. There are two camps: civilians who fight for freedom and civilians who are rebels and Fascists. All the workers in Spain know that if fascism triumphs, it will be famine and slavery. But the Fascists also know what is in store for them when they are beaten. That is why the struggle is implacable and relentless. For us it is a question of crushing fascism, wiping it out and sweeping it away so that it can never rear its head again in Spain. We are determined to finish with fascism once and for all. Yes, and in spite of the government,” he added grimly.

”Why do you say in spite of the government? Is not this government fighting the Fascist rebellion?” I asked with some amazement.

”No government in the world fights fascism to the death. When the bourgeoisie sees power slipping from its grasp, it has recourse to fascism to maintain itself. The Liberal government of Spain could have rendered the Fascist elements powerless long ago,” went on Durruti. ”Instead it temporized and compromised and dallied. Even now, at this moment, there are men in this government who want to go easy with the rebels. You never can tell you know,” he laughed, ”the present government might yet need these rebellious forces to crush the workers’ movement.”

[…]

“Can you win alone?” I asked the burning question point-blank.

Durruti did not answer. He stroked his chin. His eyes glowed.

”You will be sitting on top of a pile of ruins even if you are victorious,” I ventured, to break his reverie.

”We have always lived in slums and holes in the wall,” he said quietly. ”We will know how to accommodate ourselves for a time. For, you must not forget, we can also build these palaces and cities, here in Spain and in America and everywhere. We, the workers. We can build others to take their place. And better ones. We are not in the least afraid of ruins. We are going to inherit the earth. There is not the slightest doubt about that. The bourgeoisie might blast and ruin its own world before it leaves the stage of history. We carry a new world here, in our hearts,” he said in a hoarse whisper. And he added: “That world is growing in this minute.”

-”Durruti: The People Armed,” Abel Paz

Throughout much of the later 20th century, the global squatting movement was one of the chief lines of transmission via which anarchism was passed from one generation to the next, literally subsisting in the ruins. If anarchist ideas are spreading to new demographics today, it is partly thanks to the efforts of those generations of squatters and eco-saboteurs, to whom we dedicate this poster.

“Let us therefore trust the eternal Spirit which destroys and annihilates only because it is the unfathomable and eternally creative source of all life. The passion for destruction is a creative passion, too.”

-Mikhail Bakunin, “Die Reaktion in Deutschland,” Deutsche Jahrbücher fur Wissenschaft and Kunst, nos. 247–51